Various types of melanoma exist, such as acral, cutaneous, mucosal, and uveal, with additional microscopic subtypes that further divide these categories. Although these types are extremely different, they all share a common umbrella term – melanoma – that makes it sound like they are identical. Vocabulary is actually one of the few commonalities. Although all of these cancers arise within melanocyte cells, each occurs in a different location, has wildly different behavior, and needs treatments specific to the tumor and surrounding tissue.

Conjunctival melanoma and uveal melanoma are the two main types of ocular, or eye, melanoma. Uveal melanoma is far more common than conjunctival melanoma, yet it only represents 5% of all melanomas diagnosed, compared to cutaneous (also known as skin melanoma), where 90% of melanomas appear. (Chattopadhyay 2016) In the US, there are approximately 1,500-1,700 cases of uveal melanoma each year. (NCI; Singh 2011) Although there may be permanent changes to vision, for at least half of these cases, the cancer is treatable.

Dr. Nathan L. Scott, MD, MPP, an expert at the University of California San Diego’s Viterbi Family Department of Ophthalmology and Shiley Eye Institute, explains more about this rare type of melanoma.

What is uveal melanoma?

Uveal melanoma is a malignant cancer specific to pigmented cells inside the eye. These pigmented cells are called melanocytes. When they develop a mutation, grow uncontrollably, and have the potential to spread to other areas, we call this uveal melanoma.

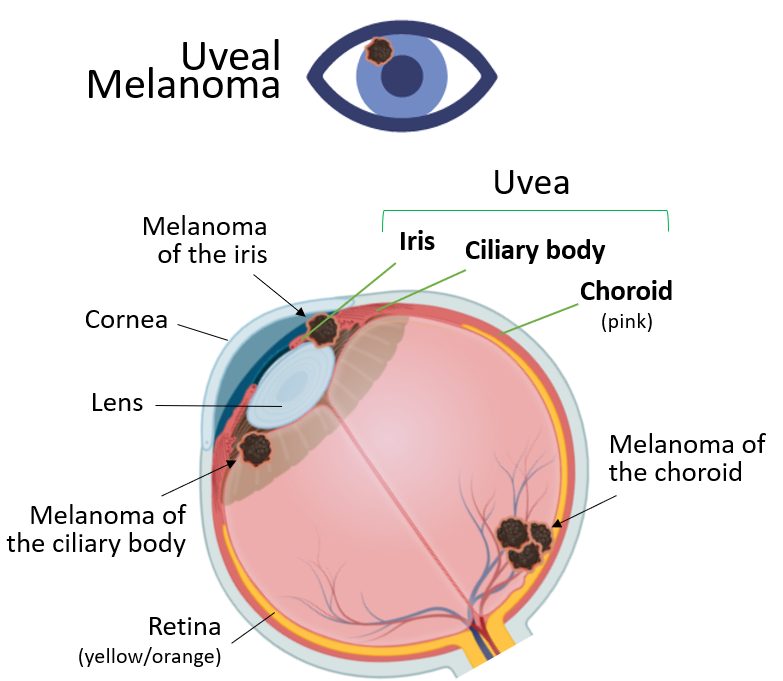

The uvea consists of 3 structures inside the eye: the iris, which is the color part of the eye; the ciliary body, which is the organ that creates the fluid that’s inside of the eye; and the choroid, which is a structure that sits underneath the retina. Those three structures—the iris, ciliary body, and choroid—are called the uvea. (Figure) The uvea contains the pigmented cells, the melanocytes. When one of these cells acquires a mutation that allows it to grow uncontrollably, that’s what we call uveal melanoma.

What are the symptoms of uveal melanoma? What is usually the first sign?

There are various symptoms associated with uveal melanoma. It may start with vision loss, light flashes, blurry vision, or floaters. One of the most common things we see is no symptoms at all. The most common occurrence among the patients that I see is that they go in for an eye exam, and another provider sees a pigmented lesion, and they send the patient to me. Having no symptoms is common, although again, flashes, floaters, and blurry vision can occur.

Are there various stages?

There are different stages of cutaneous melanoma, but because uveal melanoma is typically found initially as a single tumor in the eye without spread, we focus more on tumor size and location when considering treatment. Ocular oncologists stage uveal melanoma using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which considers not only tumor size (T) and location but also regional lymph node involvement (N) and distant metastasis (M) when discussing screening and treating the entire body. Additionally, gene expression profiling obtained after biopsying a tumor plays a pivotal role in determining the severity and risk of these tumors spreading to the rest of the body.

When the tumor is inside the eye, we typically look at its location – is it in the iris, ciliary body, or choroid? Then, we look at its size and apply the measures of small, medium, or large. The size criteria describe the tumor and are necessary to determine the type of treatment that will be employed. At the time of treatment or before treatment, we biopsy the tumor to determine how aggressive the tumor may be.

Can uveal melanoma be treated or cured?

Uveal melanoma can absolutely be treated in the eye. The most common treatment in the US is radioactive Iodine-125 seed implantation brachytherapy. This is a type of radiation that uses a gold plaque. We insert radioactive seeds inside the plaque and place it on the eye. It stays on the eye for 3-7 days and is then removed. Most centers have approximately a 96-98% single-surgery success rate. In most cases, that cures the eye of uveal melanoma.

For iris tumors and some tumors that can be surgically removed, another treatment for patients with uveal melanoma includes using lasers for small melanomas – although this is somewhat controversial. Some patients will receive proton beam therapy, which is an external radiation. If a tumor is so large that radiation therapy will cause more harm than benefit, we will remove the eye.

Unfortunately, 50% of uveal melanoma patients will develop metastasis. This is because early on in the development of the disease, melanoma cells likely escape from the tumor in the eye and find a home somewhere else—most commonly in the liver. It is 5-10 years later that some patients will develop metastatic tumors in the liver, even though the tumor in the eye is cured.

The metastasis is most likely spread through the blood, but not the lymphatic system like many other types of cancer. Most other cancers allow an assessment of a patient’s lymph nodes to determine the disease’s spread, but not uveal melanoma. The uniqueness about the spread of uveal melanoma is that 90% of the time it goes into the liver. There is some type of organ tropism (selective organ preference by uveal melanoma cells) for the liver. It is not understood why uveal melanoma targets the liver.

Special Note: The FDA has approved two drugs for certain patients to treat advanced uveal melanoma. One drug is Kimmtrak (tebentafusp-tebn) which is approved for adult patients with HLA-A*02:01-positive unresectable (meaning it can’t be removed with surgery) or metastatic uveal melanoma. Eligibility for Kimmtrak (tebentafusp-tebn) is determined by a blood test that detects the HLA-A*02:01 antigen. Another drug, Hepzato (melphalan) is approved for adult patients with uveal melanoma and used as a liver-directed treatment for patients meeting several conditions. These include having unremovable tumors in the liver affecting less than 50% of the liver and no extrahepatic disease, or extrahepatic disease limited to the bone, lymph nodes, subcutaneous tissues, or lung that is amenable to resection or radiation. Your healthcare provider can determine eligibility for either drug.

What’s the biggest misconception about uveal melanoma you hear?

The most common misconception I hear about uveal melanoma when speaking with my patients is that it overlaps with cutaneous (skin) melanoma. Very often, people have Googled information about “melanoma,” which usually gives information about cutaneous melanoma, not uveal melanoma, before they are referred to my office for a visit. Most all of this information pertains to skin melanoma and is not relevant.

The only real relationship between uveal melanoma and cutaneous melanoma is that the cancer comes from melanocytes. There are melanocytes in the skin and melanocytes in the eyes. Otherwise, they are completely different.

It is not thought that UV radiation increases the risk of most uveal melanomas, whereas UV exposure is a definitive factor for cutaneous melanoma. Otherwise, the genetic mutations we find in each type of melanoma are completely different. In terms of metastasis, the places that they go are completely different. The way that we treat them is completely different. The prognosis is also completely different for uveal melanoma versus skin or cutaneous melanoma.

What is known about prevention?

There is not much known about prevention. We live in a world where early detection is vital for prevention. It is important to get annual eye exams and have your eyes dilated when a retina specialist examines them. Certain conditions may increase your risk for uveal melanoma. For example, a condition called oculodermal melanocytosis, when individuals have brown, blue, or gray patches or pigments on the skin around their eyes, confers a higher risk.

Individuals with an abundance of skin nevi may also have an increased risk of uveal melanoma. The risk occurs even though the skin tissue is very different from the eye. With these conditions, the individuals have a genetic increase in the number of melanocytes in their skin and eyes, which numerically confers a higher risk for melanoma and glaucoma.

Although there are few preventative measures for uveal melanoma, wearing sunglasses is crucial. UV protection of the eyes is essential because individuals may have other conditions that manifest as a result of damage to the eyes from too much sun exposure. It is important that people wear sun protection to block UVA and UVB rays and take appropriate action to limit UV exposure.

What is the number one takeaway you want people to know from reading this article?

The most important thing is to make sure that you are getting your eyes checked. The difference between a small uveal melanoma versus a large uveal melanoma is huge. The differences are in how the tumors are treated, including the radiation dose, and the chance that cancer cells have not migrated outside the eye. The earlier uveal melanoma is caught, the more likely it is that cancer cells have not metastasized. This difference is significant.

Early eye exams are essential if you are told you might have a freckle or “nevus” inside your eye. If this is something that you are told, it is important to see an ocular oncologist to be sure. Do not take the word of a non-specialist provider that everything is normal.

I can’t stress enough the importance of following up in this case. One of the more common things that I see is perhaps someone was told they had a freckle in their eye 15 years ago. By the time they see a specialist to follow up, this freckle has grown very large.

Another aspect of treatment is radiation. It does a great job of treating and eliminating uveal melanoma. However, it also does a lot of damage to the normal structures in the eye. Specialists will try to help prevent vision loss by performing medical injections into the eye to prevent the damage associated with radiation. The larger the tumor, the more radiation you get, and then the higher the likelihood that you will need injections for the rest of your life to save your vision. To try and avoid that is paramount. Screening and getting an eye exam can help avoid all of this.

About our Guest

Nathan L. Scott, M.D., M.P.P. is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Ophthalmology and the Chief of the Ocular Oncology Division at the Shiley Eye Institute and Viterbi Family Department of Ophthalmology. He treats general and complex vitreoretinal diseases as well as both surface and intraocular malignancies.

Dr. Scott earned his medical degree at Harvard University Medical School and completed his residency in ophthalmology at the University of Miami Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, where he was also selected as Chief Resident. He completed fellowships in Vitreoretinal Surgery and Ocular Oncology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. He received multiple awards during his training, including the Heed Ophthalmic Society Fellowship, the Mary August Trust Fellowship Award, the 2020 Vit Buckle Society Fellows Foray award, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology Robert Copeland Fellowship award.

Dr. Scott is actively engaged with the American Academy Ophthalmology, where he serves on the executive board of the Minority Ophthalmology Mentoring program and is a member of the Young Ophthalmology Advocacy sub-committee.

Dr. Scott is a physician-scientist with a clinical focus on vitreoretinal diseases and surgery, as well as a special interest in ocular oncology. His clinical research and interests include utilizing imaging and genomic/molecular technologies to better understand, diagnose and treat cancers of the eye.

Recent Posts

From a Scare to Awareness: Lindsay Willis’s Mission to Educate on Melanoma Risks

Everything Coming up Rosy is not a Health Tune

Ways to Give: How You Can Donate Your Birthday Through Facebook

Beyond the Clinic Podcast: Navigating the Storm: Managing Stress and Anxiety Through Your Cancer Journey