In Plain English: Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocyte (“TIL”) Therapy for Advanced Melanoma

By Kim Margolin, M.D., FACP, FASCO

Background—Immunotherapy of melanoma

The explosion of immunotherapy over the past decade has revolutionized the treatment of melanoma and nearly every other adult type of cancer. As a reminder, this form of treatment stimulates the body’s immune system to attack and kill tumor cells. Of all cancers, melanoma has benefited the most from immunotherapy, in large part because the mutations caused by extensive sun damage lead to changes in the cells that can be recognized by the immune system, particularly after stimulation by immunotherapy. Additionally, because melanoma is so resistant to chemotherapy and radiation, the relative benefits of immunotherapy are greater in melanoma patients, since they have few other choices for effective treatments.

What are TIL cells? What is TIL therapy?

TIL cells are tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are the white blood cells that are able to recognize and attack malignant cells, especially when they are stimulated with immunotherapy. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte therapy, known by the simple acronym “TIL,” refers to a treatment that involves extracting T lymphocytes from a patient’s tumor, growing them in special liquid, and giving them back to the patient via intravenous (in the vein through a needle) infusion. The factors that determine whether a patient will go into remission from TIL therapy are not well understood, but the number of cells that can be given may be an important factor, so the goal of laboratory expansion of TIL cells is usually several billion cells.

The TIL cell approach has been under investigation for nearly 35 years, starting in the mid-1980s in the laboratories at the National Cancer Institute’s Surgery Branch. There, Dr. Steve Rosenberg worked tirelessly and trained dozens of investigators (surgeons, medical oncologists, and laboratory scientists) to develop and improve on methods and outcomes of TIL therapy. While much of this research has been preclinical (in animals, where the conditions can be manipulated and the outcomes measured in much shorter timeframes than in people), an extensive series of clinical trials—testing the new therapy in people with cancer—has provided new insights. These insights include the best ways to obtain the tumor that the cells are taken from, cultivate the TIL cells, select the best cells to give back to the patient, and treat the patient with additional immune system-directed medications to optimize the anti-tumor effects of the TIL cell therapy.

Who can get TIL? How does the treatment work?

To date, the patients who have been considered candidates for TIL cell therapy have had metastatic melanoma that has already been treated with standard therapies without achieving a long term remission. This means nearly all patients have already received the small number of standard treatments currently available for advanced melanoma: both of the immune checkpoint blocking antibodies ipilimumab (Yervoy) and nivolumab (Opdivo), or pembrolizumab (Keytruda), and, if the patient’s tumor is positive for the BRAF mutation, one of the three pairs of oral medications that target malignant cells with this mutation. Some patients have also received interleukin-2 (IL-2), which stimulates immune cells, causes T lymphocytes to multiply and become activated, and provides a low level of antitumor activity in patients with melanoma. However, high doses of IL-2 can also cause a lot of (reversible) side effects and dangers to the patient.

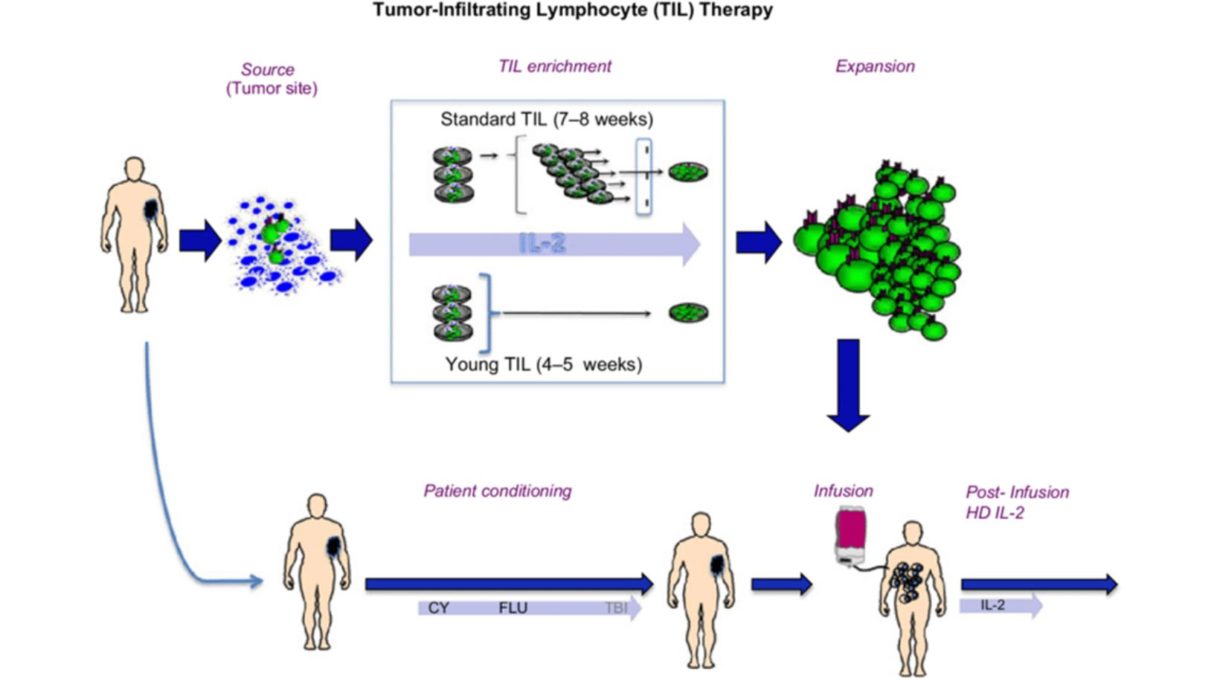

The TIL cell regimen begins with patient assessment, making sure that candidates for this therapy have a safely accessible tumor—one that can be partially or fully removed with a small surgical procedure. Tumors in the brain, the spinal cord, bones, and other less safely accessible locations would not qualify for TIL. Patients must also be in generally good medical and physical condition, which means they are judged by their doctor to be healthy enough to get through all phases of the regimen, which is shown in the diagram below and explained in the next section.

The next step is extracting and growing the TIL cells from the patient’s tumor and growing them as described above. Then the patient must be prepped for the process of infusion, which currently requires the administration of two chemotherapy drugs over five days. These drugs do not kill melanoma cells but lower the patient’s own lymphocyte count, which the body counters by increasing its levels of growth factors that will stimulate the incoming TIL cells to expand and acquire more anti-melanoma activity. After the TIL cells are given, a few doses of IL-2 are administered to keep stimulating and growing the TIL cells inside the body.

Other details of TIL cell therapy are similar to any form of combination chemotherapy and immunotherapy with highly potent drugs, including antibiotics, blood transfusions if needed, and very close supervision by doctors and nurses to minimize the risks associated with the cells going in and the side effects of IL-2.

What are the most current results of TIL cell therapy?

Most of the published results of TIL cell therapy for melanoma have come from the National Cancer Institute Surgery Branch mentioned above; additional data are from a small number of cancer centers, mostly in the U.S., who participated in multi-site studies of TIL cells for melanoma patients in relapse, with the goal of getting the first TIL therapy approved by the FDA.

The first trial ever to randomize TIL therapy against standard immunotherapy for melanoma patients in first relapse was reported by Haanen et al at the 2022 annual meeting of the European Society of Medical Oncology. In this study, 80 patients with similar characteristics whose melanoma was not controlled with PD-1 antibodies were randomly assigned to receive either ipilimumab or undergo TIL therapy. The results strongly favored TIL therapy, which doubled the response rate to approximately 50%, and significantly improved the complete response rate, the average time before tumor growth, and the percentage of patients without tumor growth at six months or longer following the initiation of therapy. Most recently, at the November, 2022 annual meeting of the Society for the Immunotherapy of Cancer, another trial was reported by Sarnaik et al, who led a trial of TIL cell therapy for advanced melanoma patients who had failed to benefit from standard therapy for advanced melanoma. In this group of 153 patients, the overall response rate was 31%, with 6% of the patients achieving a complete response and the median (time point at which half the values were longer and half were shorter) duration of response being over two years. While this form of therapy has a long way to go in terms of curing patients with melanoma that is resistant to standard therapies, it may find a place earlier in the treatment of patients who are predicted not to achieve long-term benefit from other treatments. Studies are ongoing to identify those patients as well as to make the TIL cell therapy less complex and more widely available.

While these exciting results for TIL cell therapy as an option and a hope for patients who do not achieve long term benefit from standard immunotherapy are likely to lead to an FDA approval and then further studies to improve TIL therapy even more, there remain many questions and potential obstacles. The practical ones concern the exorbitant cost of cell therapy—but considering that cell therapy is a “one and done” strategy, it may not prove to be more expensive than less complex treatments. The length of time required to prepare the TIL cell product has also gone down as laboratory advances are made—currently only about three weeks. Access to centers with experience who can perform this therapy may be challenging, but unlike the original form of anti-malignancy cell therapy—bone marrow transplantation—TIL therapy does not require a donor. More important clinical issues that oncologists and laboratory investigators are still grappling with are the high initial drop-off rate (the trial detailed above actually entered twice as many patients as eventually went on to get treated) and what to do about growing and freezing TIL from patients who may not need them at the time but may need them in the future for possible relapse.

Taken together, the pooled results of TIL cell therapy from a number of U.S. and ex-U.S. centers as well as the industry-sponsored studies are remarkably good, considering that these studies most often enrolled patients who had exhausted all other therapies with known benefit. If patients whose melanomas are resistant to available immunotherapy and targeted therapies can still achieve long-term remissions from another form of immunotherapy like TIL, it is highly likely that we can expect to cure a substantially larger percentage of melanoma patients.

The next question to answer is whether we can identify in advance those patients who will not benefit from currently available therapies (immunotherapies and targeted therapies) but will benefit from TIL cell therapy and give those patients TIL treatment earlier in their diagnosis and without having to receive the other therapies first. Indeed, there are clinical trials looking at this question now. While metastatic melanoma is still a very challenging disease to treat, the options are getting better every day, and with the advent of TIL cells and other new immunotherapies, it is likely that an increasing percentage of patients with this disease will have access to therapies that could cure their disease.

Of course, the rising tide lifts all boats. While TIL cell and related strategies are being worked on to improve their outcomes, safety, lower costs and enhance accessibility, other treatments for melanoma and other cancers are also in the works. Competition is good, as it brings out the creativity of scientists and the enthusiasm of clinical investigators. It is possible that sometime in the near or distant future, TIL cell therapy will have become not only commonplace but maybe even obsolete, moving aside in favor of treatments that are even more effective, safe, cheap and well-tolerated. Look for those advances in coming issues of “In Plain English.”

Questions on this article may be submitted to Alicia@AIMatMelanoma.org

Dr. Margolin is a Medical Director of the SJCI Melanoma Program, St. John’s Cancer Institute. She worked at City of Hope for 30 years and also held faculty positions at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance/University of Washington and at Stanford University. Among her academic achievements were long-term leadership of the Cytokine Working Group, leadership involvement in the Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network, participation in the Southwest Oncology Group’s Melanoma Committee, and many positions in the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer. Dr. Margolin has reviewed grants for many cancer-related nonprofit organizations and governmental agencies. She has also served as a member of the Oncology Drugs Advisory Committee to the FDA, the American Board of Internal Medicine’s Medical Oncology certification committee, and the Scientific Advisory Committee of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer.

Dr. Margolin collaborates with AIM at Melanoma to write our In Plain English articles to provide timely updates on new developments for patients, caregivers, and other individuals with an interest in medical advances in melanoma.

Recent Posts

A Conversation with Dr. Rena Szabo, PsyD on Empowering Patients

Empowering Women in Melanoma: A Look Inside the Women in Melanoma Initiative

Melanoma News and Highlights You Don’t Want to Miss

Coping with Cancer: DBT Skills for Emotional Resilience