Ocular Melanoma

What is Ocular Melanoma?

Ocular melanoma is a rare form of melanoma that occurs in the eye. Though it develops from melanocytes, the same cell that causes melanoma in the skin, it should be considered a separate cancer from skin melanoma.

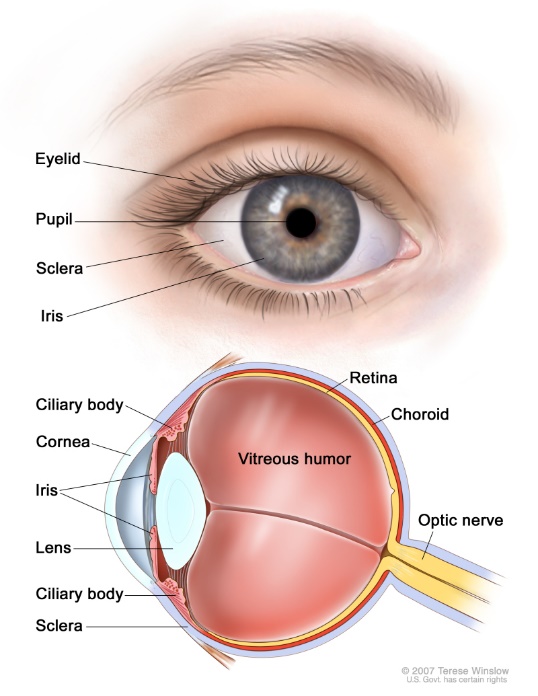

Ocular melanoma most often affects the middle layer of your eye (the uvea), which includes the colored portion (the iris), the muscle fibers around the lens (ciliary body), and the layer of blood vessels that lines the back of the eye (choroid).

Melanoma can also develop in the conjunctiva, the clear tissue that covers the white part of the eye and the inside of the eyelids.

Melanoma that develops in the choroid, iris or ciliary body is called uveal melanoma, and melanoma that develops in the conjunctiva is called conjunctival melanoma. Although both develop in the eye, these two diseases are biologically and clinically different from one another, and both are very different from the more common form of melanoma occurring on the skin. Because the majority of ocular melanoma cases are uveal, sometimes people refer to ocular melanoma as uveal.

Both types of ocular melanoma are rare. Uveal melanoma is diagnosed in about 2,500 people each year in the U.S.—but it is the most common primary cancer of the eye in adults. Median age of onset is about 60 years old, but it can occur at any age. Conjunctival melanoma is even more rare with likely incidence of < 1 cases per million people.

Uveal Melanoma

Some cases of uveal melanoma are diagnosed during a routine eye exam without the patient having any symptoms, other patients develop symptoms that prompt them to get an eye exam, and some patients have a freckle on the choroid that is followed and changes over time. The most common treatments for uveal melanoma are radioactive plaques, proton beam therapy, or removal of the eye. Primary treatment of uveal melanoma is very effective with recurrence in the eye happening in less than 5% of cases. However, despite the primary tumor being controlled there is a risk of the melanoma returning outside of the eye. The risk of the melanoma returning can be estimated by the size of the melanoma as well as other clinical and pathological factors; by looking at changes in the chromosomes of the tumor (i.e., cytogenetic testing); and by looking at an altered pattern of genes that are expressed (i.e., gene expression profiling).

About 50% of people with uveal melanoma will develop metastases. When uveal melanoma does recur, it often does so in the liver. Advanced uveal melanoma is a challenging cancer to treat, and a broad range of treatments can been used, including immunotherapy, molecularly targeted agents, and a number of liver-directed treatments such as bland embolization, chemoembolization, immunoembolization, radioembolization, and infusion of chemotherapy into the liver. The prognosis for metastatic uveal melanoma patients has historically been quite poor, with limited overall survival.

The good news for uveal patients is that in January 2022, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Kimmtrak (tebentafusp-tebn) for the treatment of HLA-A*02:01-positive adult patients with unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma. Kimmtrak is the first and only FDA-approved therapy for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma (mUM). FDA approval was based on the results of a phase 3 clinical trial in which Kimmtrak showed statistically and clinically meaningful overall survival benefit for mUM patients. A total of 378 previously untreated patients were randomly assigned to either the Kimmtrak (tebentafusp) group (252 patients) or the control group (126 patients). The control group received single-agent treatment with pembrolizumab (82% of control patients), ipilimumab (13%), or dacarbazine (6%). Overall survival (OS) at one year was 73% in the tebentafusp group and 59% in the control group.

Click here to learn more about Kimmtrak.

Conjunctival Melanoma

Conjunctival melanoma is more rare than uveal melanoma. It has no clear cause, and it usually appears as a pigmented spot on the outer surface of the eye. Individuals diagnosed with conjunctival melanoma commonly have a resection of the melanoma by an ophthalmologic oncologist and may receive further treatments to the eye such as cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, or radiation. Despite aggressive treatment, primary conjunctival melanoma may recur. Unlike uveal melanoma, which more often spreads to the liver, conjunctival melanoma often metastasizes to the lymph nodes and lung, its behavior much more similar to skin melanoma. There is no standard recommendation for the treatment of patients with advanced conjunctival melanoma primarily because of the rarity of the disease. Generally, these patients are treated similarly to patients with advanced skin melanoma, using immunotherapy and targeted therapy, if applicable.

Conclusions

Despite the significant advances made in our understanding of conjunctival and uveal melanoma, these diseases are still challenging to treat. To develop more successful treatments, we must support combined efforts between patients dealing with these diseases, the doctors caring for them, and the laboratory and clinical researchers working to develop new treatments for conjunctival and uveal melanoma. It is through this kind of cooperation that we can increase education and awareness of these rare diseases and ultimately identify new, more effective, and potentially curative treatments.